I discovered something unsettling last Tuesday morning. My tomato plants were whispering.

Not literally, of course, though after three cups of coffee and two hours hunched over my raised beds at dawn, I might have been open to that possibility. What I mean is that they were communicating in a language I’d spent fifteen years ignoring: the subtle, sophisticated vocabulary of a living soil ecosystem.

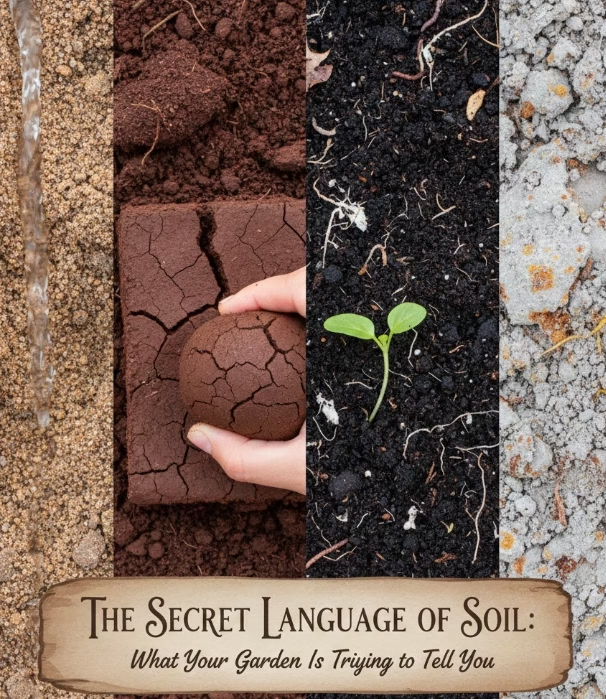

That realization changed everything about how I garden. And if you stick with me through this journey into the underground universe beneath your feet, it might change everything for you too.

The Garden I Thought I Knew

For over a decade, I treated my garden like a vending machine. Insert water, add fertilizer, press the “grow” button, receive tomatoes. It worked well enough. My Instagram feed looked respectable. Neighbors complimented my dahlias. I won second place in the community garden’s summer showcase three years running.

But something was always slightly off. My yields were okay but never spectacular. Plants would thrive one season and mysteriously struggle the next in the same location. I developed an expensive habit of buying specialized fertilizers for every plant type, convinced that the solution to better gardening was always one more product away.

Then I met Harold.

Harold’s Heresy

Harold is seventy-eight years old, grows vegetables that look like they’ve been photo-enhanced, and hasn’t purchased fertilizer since 1987. When he told me this at a seed swap last spring, I assumed he was either lying or lucky enough to live on some kind of magical ancestral farmland.

“Come see my yard,” he said. “I’ll show you my secret.”

I expected some quirky grandpa trick, a weird compost recipe involving fish heads or a moon-planting calendar. What he showed me instead was a mason jar full of dirt.

“Look closer,” he instructed, handing me a jeweler’s loupe.

What I saw through that magnifying lens rewrote my understanding of what a garden actually is. The soil was alive—and I don’t mean in the vague, poetic sense we usually use that phrase. It was a thriving metropolis. Tiny arthropods scrambled across particles of organic matter. Microscopic threads of fungal hyphae wove through the sample like a subway system. The “dirt” I’d been treating as an inert growing medium was actually a complex, breathing, interconnected community.

“Your plants aren’t just sitting in soil,” Harold explained. “They’re participating in the most sophisticated agricultural technology ever developed—one that’s been perfecting itself for 450 million years. You just have to learn to read what it’s telling you.”

The Soil Food Web: Your Garden’s Operating System

Here’s what they don’t tell you in most gardening books: your plants are not individuals. They’re nodes in a network.

Beneath every garden lies an invisible wood-wide web of mycorrhizal fungi, microscopic organisms that colonize plant roots and extend their reach exponentially. A single teaspoon of healthy garden soil contains more living organisms than there are people on Earth. These aren’t passive residents; they’re active collaborators in an exchange economy that makes Wall Street look primitive.

Plants produce sugars through photosynthesis, that much we learned in school. What we weren’t taught is that they pump up to 40% of those hard-earned sugars out through their roots as exudates, essentially feeding the soil. Why would they do something so seemingly wasteful?

Because they’re shopping.

Those root exudates attract specific bacteria and fungi. In return, these microorganisms break down organic matter and minerals in the soil, making nutrients available to the plant in forms it can actually absorb. The fungi extend the root system’s effective reach by thousands of times. Bacteria produce growth hormones, suppress pathogens, and even communicate pest threats through chemical signaling.

This is regenerative agriculture in its most elemental form, and it’s happening whether we know about it or not. The question is: are we supporting it or sabotaging it?

Reading the Signs: What Your Garden Is Actually Saying

Once Harold taught me what to look for, I started seeing signs everywhere. My garden had been screaming at me for years; I’d just been too busy following conventional wisdom to listen.

Sign #1: The Compaction Blues

Remember those tomatoes I mentioned? The ones that were “whispering”? What caught my attention that Tuesday morning was how they’d started growing their roots horizontally along the surface rather than down into the soil.

This is your garden’s way of saying: “I literally cannot breathe down there.”

Soil compaction is the silent killer of gardens. When soil particles get packed too tightly, usually from tilling, heavy foot traffic, or working wet soil—the air spaces between particles collapse. Those spaces are crucial. Plant roots need oxygen. So do the billions of microorganisms that make nutrients available. When soil compacts, the entire underground economy grinds to a halt.

The fix isn’t more fertilizer. It’s more air. I stopped tilling entirely (more on that later) and started adding compost as a top mulch rather than mixing it in. Within six weeks, I could push a finger deep into soil that previously resisted a shovel.

Sign #2: The Weed Oracle

I used to view weeds as enemies. Now I see them as unpaid consultants.

Different weeds thrive in different soil conditions, and their presence tells you exactly what’s happening underground. Dandelions proliferate in compacted, heavy soils—they’re nature’s soil aerators, driving their taproots deep to break up hardpan. Chickweed flourishes in soil with high nitrogen and low calcium. Clover fixes nitrogen, appearing in nitrogen-deficient areas and solving the very problem that allowed it to outcompete other plants.

When I noticed a patch of my garden becoming dominated by sorrel and dock, I didn’t reach for herbicide. I reached for a pH test kit. Sure enough, those areas had become strongly acidic. Rather than treating the weeds, I treated the condition that caused them: I added lime to raise the pH and sheet-mulched with cardboard and compost. The weeds gradually disappeared as more desirable plants found the conditions favorable again.

Weeds aren’t problems. They’re symptoms. More importantly, they’re solutions-in-progress.

Sign #3: The Color Commentary

Plant leaves are the most honest reporters in your garden. They cannot lie, and they cannot hide deficiencies.

Yellowing leaves with green veins? That’s chlorosis, usually indicating iron deficiency, but adding iron often won’t help if your pH is too high for plants to access it. Purple-tinged leaves might mean phosphorus deficiency, but that’s often a symptom of cold soil or, again, pH issues that lock up available phosphorus.

Here’s the revolutionary realization: most nutrient deficiencies in gardens aren’t caused by nutrients being absent. They’re caused by nutrients being present but unavailable. The nutrients are there; your plants just can’t access them because the soil chemistry or biology is off.

This is why Harold hasn’t bought fertilizer in nearly forty years. He’s not starving his plants, he’s feeding his soil’s ability to feed his plants. There’s a crucial difference.

The No-Till Revelation

Of all the lessons Harold taught me, this was the most controversial and the most transformative: stop digging.

I know. It feels wrong. Tilling has been synonymous with gardening for so long that suggesting we stop feels like heresy. But here’s what happens when you till:

You destroy fungal networks that took all season to establish. Those mycorrhizal highways I mentioned? A single pass with a tiller obliterates months of biological infrastructure. It’s like demolishing a city’s entire transportation system and expecting the economy to improve.

You bring weed seeds to the surface. Every time you till, you’re exposing buried seeds to light and air, triggering germination.

You accelerate organic matter decomposition. That rapid breakdown releases a flush of nutrients (which feels good in the short term) but depletes your soil’s long-term fertility reserves.

You compact the soil below the tilled layer, creating a hardpan that roots and water can’t penetrate.

The alternative? Build up instead of digging down. Add layers of compost, leaf mold, wood chips, or other organic matter directly on the surface. Let worms and soil organisms do the tillage for you. They’re far better at it than any machine.

I converted my entire vegetable garden to no-till three years ago. The first season felt like a leap of faith. The second season showed promise. By the third season, I was growing produce that made my previous “successful” gardens look anemic by comparison. The soil went from hard-packed clay to crumbly loam that smelled like a forest floor.

The Compost Epiphany

If soil is a garden’s operating system, compost is the upgrade that makes everything run faster.

But not all compost is created equal, and most of us are making it wrong, or at least, not as right as we could be.

Good compost isn’t just rotted garbage. It’s a carefully balanced ecosystem in miniature, and the quality of your finished product depends entirely on what you put in and how you manage the process.

The Brown-Green Balance

Everyone knows compost needs “greens” (nitrogen-rich materials like kitchen scraps and grass clippings) and “browns” (carbon-rich materials like dried leaves and cardboard). Most guides recommend a 30:1 carbon-to-nitrogen ratio.

But here’s what they don’t emphasize enough: diversity matters more than ratio precision.

A compost pile made from thirty ingredients will produce richer, more biologically diverse compost than one made from three ingredients at the perfect ratio. Each input brings its own microorganisms, minerals, and organic compounds. A handful of leaf mold introduces different decomposers than a handful of rotted straw.

I started keeping a “compost inventory” log. Coffee grounds from three different cafés (different beans, different microbial profiles). Leaves from oak, maple, and birch. Vegetable scraps, crushed eggshells, shredded newspaper, wood ash in small amounts, even hair from the barbershop. My compost became a biological library, and the resulting material was dark, crumbly, and so full of life that it stayed warm for weeks even in a passive pile.

Hot vs. Cold Composting: The False Choice

Most guides present hot composting (maintaining temperatures of 130-150°F) and cold composting (passive decomposition) as two distinct methods. But I’ve found the sweet spot is a hybrid approach I call “warm composting.”

I build my piles large enough to generate heat (at least 3x3x3 feet) but don’t obsess over maintaining peak temperatures. I turn them when convenient, not on a strict schedule. The pile heats up during active decomposition, then cools as it matures. This preserves more of the beneficial microorganisms that die off in sustained high heat while still killing most weed seeds and pathogens.

The result is compost that’s biologically alive rather than sterilized, and when you add it to your garden, you’re not just adding nutrients but also inoculating your soil with beneficial organisms.

The Mulch Revolution

If I could give just one piece of advice to transform someone’s garden overnight, it would be this: cover your soil.

Bare soil is an emergency in nature. It’s a wound that the earth immediately tries to heal by sending in pioneer species (what we call weeds). Bare soil loses moisture, temperature-regulates poorly, and bleeds nutrients with every rain.

Mulch is the solution to dozens of gardening problems simultaneously:

Water retention: Mulched soil holds moisture far longer than bare soil. I cut my watering by more than half after mulching consistently.

Temperature regulation: Mulch insulates soil, keeping it cooler in summer and warmer in winter. This extends the growing season and protects root systems.

Weed suppression: A 3-4 inch layer of mulch blocks light from reaching weed seeds, preventing germination. The weeds that do appear pull easily from the soft, moist soil beneath.

Soil building: Organic mulches gradually decompose, constantly feeding the soil surface with fresh organic matter.

Erosion prevention: Mulch protects soil from the pounding impact of rain and irrigation.

But here’s where it gets interesting: different mulches create different soil conditions.

Wood chips are excellent for pathways and around perennials, but their slow decomposition rate means they don’t add much fertility quickly. Compost mulch feeds soil rapidly but breaks down quickly and may need frequent replenishment. Leaf mold is the Goldilocks option—it improves soil structure beautifully while providing moderate nutrition.

I’ve started using different mulches strategically. Wood chips on paths and around shrubs. Compost around heavy feeders like tomatoes and squash. Leaf mold for perennial beds. Straw for annual vegetables. Each creates its own micro-ecosystem, attracting different beneficial organisms.

The Water Paradox

Here’s a confession: I used to water my garden every day during summer. I was proud of my consistency. I was also drowning my plants.

Frequent shallow watering does several harmful things:

It encourages roots to stay near the surface, making plants vulnerable to drought and heat stress.

It creates conditions for fungal diseases by keeping foliage damp.

It leaches nutrients below the root zone.

It trains you to be a servant to your garden rather than the other way around.

Harold’s garden goes weeks without supplemental water in summer. How? Deep, infrequent watering that encourages deep root growth, combined with heavy mulching that preserves soil moisture.

I switched to watering deeply once or twice a week instead of daily light sprinkling. I also started paying attention to when I water. Early morning is ideal—plants can dry before nightfall, reducing disease pressure. Evening watering leaves plants damp overnight, inviting fungal problems.

But the real breakthrough came when I installed a simple soil moisture meter. Turns out my instinct about when plants needed water was wrong about 60% of the time. The soil surface looked dry, but six inches down, there was plenty of moisture. I was watering out of anxiety, not necessity.

The Diversity Doctrine

Monocultures are biological deserts. Even if that monoculture is tomatoes.

In nature, you never see single-species plantings. Forests contain dozens of species in a single square meter. Prairies are tapestries of grasses, forbs, and flowers. This diversity isn’t decorative; it’s functional.

Different plants attract different beneficial insects. They pull different nutrients from different soil depths. They cast different root exudates that feed different soil microorganisms. They provide physical structure that creates microclimates and habitat.

I tore out my neat rows three years ago. Now my garden looks gloriously chaotic—and it’s healthier than ever.

Tomatoes grow next to basil (pest deterrent) and borage (pollinator attractor). Carrots nestle alongside onions (pest confusion). Beans climb cornstalks while squash spreads between them, recreating the indigenous “three sisters” polyculture. Nasturtiums scramble through everything, serving as trap crops for aphids.

The insect life exploded. Not just pests, but predators: ladybugs, lacewings, parasitic wasps, spiders. I haven’t used pesticides—not even organic ones—in two years. The ecosystem regulates itself.

This approach, called companion planting or polyculture, also confuses pests. Many insects locate their preferred plants by smell or sight. When target plants are interspersed with other species, pests simply can’t find them as easily.

The Perennial Perspective

Annual vegetables get all the glory in garden magazines. But the smartest thing I ever did was dedicate a third of my garden to perennial food crops.

Asparagus, rhubarb, artichokes, perennial onions, berry bushes, fruit trees—these plants represent a fundamentally different relationship with gardening. You plant once and harvest for years or even decades.

More importantly, perennials build soil rather than depleting it. Their extensive root systems, some reaching deep into the subsoil, pull up minerals that annual vegetables can’t access. When their leaves die back, those minerals return to the surface, enriching the topsoil.

Perennials also provide continuous habitat for beneficial organisms. Annual vegetable beds get cleared and replanted, disrupting the soil ecology each time. Perennial beds remain undisturbed, allowing complex food webs to establish.

My perennial beds are the healthiest parts of my garden, requiring the least input and producing the most reliable yields. They’re also significantly less work—no annual starting seeds, transplanting, or clearing spent plants.

The Observation Practice

The single most powerful technique Harold taught me wasn’t about compost recipes or planting schedules. It was about attention.

“Spend ten minutes in your garden every morning,” he said. “Not working. Just looking.”

This felt wasteful at first. I had weeds to pull, plants to stake, harvesting to do. But I committed to it, and those morning observation sessions transformed my gardening more than any other single practice.

I started noticing patterns I’d missed for years. That particular corner that stayed damp even in drought—perfect for lettuce in hot months. The section that got afternoon shade from the neighbor’s tree—ideal for cool-season crops extended into summer. The way aphids always appeared first on one specific rose bush—a sentinel plant that gave me early warning before they spread.

I noticed which plants consistently thrived and which struggled in the same locations year after year. I observed how water flowed across my garden during heavy rain, revealing drainage patterns that explained mysterious wet and dry spots.

Most importantly, I stopped reacting and started anticipating. Problems became visible when they were small and manageable. Opportunities revealed themselves—a volunteer tomato in the perfect spot, a self-seeded herb creating an unexpected beneficial companion planting.

Keep a garden journal. Note what you observe, what you do, and what happens. Over time, patterns emerge that are invisible in the moment but obvious in retrospect. My journal has become the most valuable reference I own, far more useful than any gardening book because it’s specifically calibrated to my unique conditions.

The Failure Factor

Let’s talk about my spectacular disasters, because they taught me more than my successes.

Three years ago, I decided to grow heirloom melons. I researched varieties, started seeds indoors under lights, hardened off seedlings properly, and transplanted them into rich soil with trellises for support. I did everything right.

They all died. Not sick, not stunted—completely dead within three weeks.

I was devastated. I’d failed at something that’s supposedly beginner-level. Then I did a deep dive into my specific conditions: heavy clay soil that, despite amendments, still held water too long in spring. Melons need excellent drainage and warm soil. My garden couldn’t provide either in the microclimate where I’d planted them.

The next year, I tried melons again—but in large fabric grow bags filled with a custom sandy mix, positioned in the hottest, sunniest corner of my yard. They thrived, producing more fruit than my family could eat.

The lesson wasn’t about melons. It was about the futility of fighting your fundamental conditions. Work with what you have, not against it.

I have a shady yard? I grow shade-tolerant crops and celebrate them instead of struggling with sun-lovers. I have heavy clay? I grow plants that tolerate clay and focus on long-term soil improvement rather than quick fixes. I have short seasons? I choose early varieties and use season extension, rather than mourning long-season crops that will never work here.

Every failed plant is information. It’s the garden telling you something about conditions, timing, or compatibility. Stop seeing failure as personal inadequacy. Start seeing it as data.

The Minimal Intervention Philosophy

The more I learned about soil ecology and plant biology, the more I realized how often my “help” was actually harm.

That fertilizer I was adding? It was providing quick nutrition but bypassing the soil food web, essentially making my plants dependent on me instead of building their ability to feed themselves. The more I fertilized, the more I had to fertilize.

That pest spray—even the organic neem oil I felt virtuous about using? It was killing beneficial insects along with pests, disrupting the predator-prey balance that would have eventually controlled the problem naturally.

That meticulous staking and pruning? Sometimes necessary, but often just my control issues manifesting as “good gardening.”

I’ve embraced what I call the “lazy gardener philosophy,” which is really just working with natural processes rather than against them:

I let plants self-seed. Some of my best producers now are volunteers—plants that chose their own optimal germination timing and location.

I allow some level of pest damage. A few aphids on my roses? That’s food for ladybugs. Cabbage white butterflies in the garden? Their caterpillars feed birds and wasps. Only when damage threatens plant survival do I intervene, and then minimally.

I stopped deadheading everything religiously. Yes, it can extend blooms, but it also prevents plants from setting seed. And those seeds feed birds through winter and potentially give me free plants next year.

I let leaf litter accumulate in my perennial beds. It looks “messy” by conventional standards, but it’s free mulch, winter habitat for beneficial insects, and slow-release fertilizer.

The Economics of Abundance

Let’s address the practical question: does all this soil-building and ecosystem management actually produce better yields?

In my case, unequivocally yes. But the comparison isn’t straightforward because I’m measuring different things now.

By weight, my vegetable yields have roughly doubled since adopting these practices. My tomato harvest went from about 40 pounds to over 80 pounds from the same square footage. Lettuce went from two harvests per season to continuous cutting for five months.

But the quality improved even more dramatically than quantity. The tomatoes have flavor I didn’t know tomatoes could have—complex, sweet-tart, intensely aromatic. The lettuce is crisp and sweet without bitterness. The herbs are so potent I use half as much in recipes.

My neighbors joke that I’ve figured out how to grow “organic-plus” produce. The secret is that truly healthy plants, growing in living soil with balanced nutrition, simply taste better. They produce more of the secondary metabolites—flavonoids, terpenes, polyphenols—that create flavor and nutrition.

I’m also spending dramatically less on inputs. No fertilizers, no pesticides, minimal water usage. My primary expense is compost materials, and most of those are free—leaves from neighbors, coffee grounds from cafés, cardboard from stores that are happy to give it away.

The time investment shifted but didn’t increase. I spend less time on routine maintenance (watering, fertilizing, pest control) and more time on observation, harvest, and seasonal soil building. The work feels more purposeful and less frantic.

The Climate Resilience Factor

We need to talk about why this matters beyond your backyard.

Home gardens collectively represent a massive land area—some estimates suggest 40 million acres in the US alone. How we manage those acres has real implications for climate, water, and biodiversity.

Living soil sequesters carbon. That web of fungi and organic matter we’ve been discussing? It’s actively pulling carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it underground. One study found that converting degraded soil to healthy, living soil can sequester up to one ton of carbon per acre annually.

Healthy soil holds water like a sponge, reducing runoff and recharging groundwater. In an era of increasing droughts and floods, gardens that build soil are creating resilience for entire watersheds.

Diverse plantings, especially with native species interspersed, provide critical habitat corridors for pollinators and other wildlife struggling with habitat loss.

This isn’t just feel-good environmentalism. It’s practical adaptation to changing conditions. My garden weathered a record-breaking drought last summer with minimal intervention because the soil held moisture so effectively. It survived a late spring freeze that killed neighbors’ seedlings because the soil’s insulation protected roots and allowed rapid recovery.

Gardens that work with ecological processes rather than against them are simply more resilient. They bend instead of breaking.

The Community Connection

Here’s an unexpected benefit: the more my garden thrived using these methods, the more my neighbors wanted to know what I was doing.

Harold’s knowledge didn’t stop with me. I’ve passed it on to at least a dozen other gardeners now. We’ve formed an informal network, sharing observations, resources, and surplus produce.

Someone has excellent leaf mold? We share. Another has rabbit manure from their pet? We distribute it. I have extra tomato seedlings? They go to neighbors who provide coffee grounds for my compost.

This is food security at the neighborhood level. It’s relationship building. It’s knowledge preservation.

I’ve watched a single jar of soil under a magnifying lens—Harold’s initial demonstration—ripple out into a community of gardeners who understand that healthy food comes from healthy soil, which comes from healthy practices.

The Permission to Be Human

Let me close with this: everything I’ve shared represents fifteen years of gardening and three years of intensive learning. I still make mistakes. I still have crops that fail. I still get frustrated when aphids explode or cucumber beetles decimate my squash vines overnight.

The difference is that now I understand the context. I know why things happen. I can make informed decisions instead of just following instructions from a book or bag of fertilizer.

You don’t have to implement all of this at once. Start with one practice: maybe stop tilling, or start mulching, or begin a simple compost pile. Observe what changes. Build from there.

Your soil is already alive, already talking. The question is whether you’re ready to listen.

That Tuesday morning when I noticed my tomatoes growing surface roots, I could have just staked them higher and carried on. Instead, I stopped and asked: what are they trying to tell me? That question led to understanding compaction, which led to mulching, which led to exploring soil biology, which ultimately transformed not just my garden but my entire relationship with the land I steward.

The secret language of soil isn’t really secret. It’s being spoken all around us, in every garden, every day. We’ve just forgotten how to hear it.

Harold is eighty-one now. His garden is more productive than ever. When I asked him recently what keeps him out there, still experimenting and observing after more than half a century, he smiled.

“Every year I think I’ve learned it all,” he said. “And every year the soil teaches me something new. That’s the deal—you pay attention, and it pays you back. Simple as that.”

It really is that simple. And that profound.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a date with my garden. There’s a patch of mysterious yellowing on my pepper plants that I need to investigate. I have a hunch it’s trying to tell me something important.

Are you listening to yours?